Introduction

Time, when it made you and me the

Person of the Year on Christmas 2006, challenged Thomas Carlyle’s theory

that history is shaped by the powerful and the famous. It pinpointed Web

2.0 technology as the driver of a revolution, in which we are “citizens

of a new digital democracy.” Everyone with a digital camera, it said,

now has the power to change history. The Web 2.0 world is a massive

social experiment that could fail. It may have reinvented democracy, but

at what cost to democracy? [1]

While Web 2.0 may be the new driver, the

revolution actually began in 1975 when we turned away from the pen and

the typewriter and started buying personal computers.

How do we view personal

digital practices and preservation now? And, more importantly, how are

libraries, archives and museums tackling information on private

computers and in the cloud?

A 2010

perspective

Over the past three years, digital data and

its consumption have continued to expand. There are now more than 1

billion PCs in the world, a number that is expected to grow to 2 billion

by 2014.[2]

There are about 45 gigabytes of digital information for every person on

the planet. By 2011, this is expected to grow ten-fold and it will

expand by a factor of 10 every five years. [3]

In 2008, Americans spent 12 hours a day consumed information outside

working hours. Reading, which was in decline because they were looking

at too much television, tripled from 1980 to 2008 because reading is the

overwhelmingly preferred way to process ideas on the Internet.[4]

Web 2.0 tools and

services have proliferated. Facebook has outstripped MySpace in

popularity. Bloggers, like one-day cricketers attracted to Twenty20

circuses, have become twitterers. Wikipedia and YouTube have become

routine aids for many readers and viewers.

The value of the Web 2.0 world

My thick file of press

clippings on Web 2.0 topics contains items from a number of broadsheets

that read as though they were meant for the tabloids. Social media sites

and services are addictive and vindictive. They are playgrounds for the

narcissistic. They are tools for stalkers and paedophiles. Although they

can create friendships, they inhibit real friendships. They are brimming

with inanity. You can even use them to find your next date – if you are

at an age when finding your next date is more important than being

satisfied with your old one or settling down with a good book.

John Fowles, author of

a string of notable literary best sellers and curator of the Lyme Regis

Museum, once wrote that “a diary is a place you can write the things you

dare not say in public, a place where you are free to vent your anger,

frustration and prejudice, no matter how unreasonable those feelings

might be.” And, quoting William Boyd, he observed that “No true journal

worthy of its name can be published while the author is alive. Only a

posthumous appearance guarantees the prime condition of honesty.”[5]

But Elizabeth Farrelly detects a shift in the attitudes of younger

generations in her observation that the internet is a place for a new

kind of exhibitionism, a place “where young people are willing to expose

failures and vulnerabilities to an unfiltered, even hostile audience.”[6]

Social media

technologies can lead to wasted time. In fact, knowledge management

pioneer, Tom Davenport says they are among the greatest time wasters of

the age.[7] John

Freeman proffers a reason: the simulated busyness of email addiction is

actually numbing an inner pain. The internet is not a world unto itself,

he reminds us, but a supplement to our existing world. Trading the

complicated reality of friendship for a vacuum-packed idea is not a good

idea. Context matters, so if electronic communication has stopped

providing it, we should turn back to the real world for a solution and slow down.[8]

Some feel social media

will do irrevocable damage to mainstream media. They fear that

newspapers will lay off experts in the face of competition from

bloggers. Citizen journalists mainly use, at no cost, regurgitated news

from old media. Hardly any of them break news themselves. If mainstream

media begins retrenching skilled journalists, the rot will have set in.

In debunking the value

of social media, some predict that a preoccupation with it will cause

the decline of civilisation. John Freeman laments the fact that we are

turning the “once-eloquent art of writing into a behaviour that

encourages a torrent of self-absorbed output at the expense of

introspection.”[9]

Ben McIntyre agrees: real storytelling is being drowned out and we are

being led into an anorexic form of culture.[10]

Andrew Keen, while acknowledging that the Web has increased the

availability of knowledge hugely in our favour, says the views of the

expert do trump the collective wisdom of amateurs: “although it is

enticing to believe that online diaries are empowering, the hype is

dangerous.”[11]

But, if we turn to the

internet itself – to Wikipedia – we find a semblance of balance. The

internet and social media have made possible entirely new forms of

interaction, activities and ways of organising things. They have

generated new forms of leisure. They have been successfully used in

political campaigning and government communication, in education, in

emergencies, in public relations, in gathering opinion, in space

exploration. Jonathan Zittrain, professor of Internet law at Harvard Law

School leans towards a positive view: "the qualities that make Twitter

seem inane and half-baked are what makes it so powerful."[12]

And George Megalogenis, in a recent piece about its use in political

contexts, sums it up this way: “The content may be banal, but these are

the conversations that will define an era and help decide the next

election."[13]

Personal habits

Personal habits are

changing. In the age of the digital camera, the story of almost everyone

can be more easily captured from birth to death. Ordinary people have

mounted the same stage as the famous. There are fewer degrees of

separation. Websites have replaced gravestones.[14]

In the old days, the

famous scribbled away during their lifetime and their jottings were

published after their death. If Jane Welsh Carlyle, George Orwell,

Philip Larkin and John Fowles had lived in a Web 2.0 world, would their

diaries and letters have been as revealing if they had joined Facebook?

If the reclusive Stanley Kubrick had been born in 1948 instead of 1928,

would he have still left behind the goldmine of his one thousand boxes?

And, if Emily Dickinson had lived between 1986 and 2042, would she have

published in her lifetime all 1775 poems, instead of the seven that

reached the public arena before she died in 1886?

Helen Mirren’s recent

autobiography highlights richness in the way lives are now presented as

digitally-produced products. Images in the book – happy snaps and

professional photos – are accompanied by pictures of letters, family

trees, school compositions, wartime ration cards, houses lived in,

theatres performed in, press clippings and travel documents.[15]

The biographer has become curator and exhibitor.

Every person has a

story to tell. Every town has a Diaspora of prodigal sons and daughters.

My own scrapbooks, now with digitised memorabilia, have family trees,

the photographs of immigrant antecedents, old houses, old schools, past

teachers, fellow students whose names have been forgotten, community

theatre programs and influential record covers. But they also contain

unique images and text, not yet captured in public institutions, about

notable Australian artists, writers and entertainers. A relatively

unimportant digital photograph of me in a winning suburban cricket team

during the mid-1960s is somehow now retrievable from a regional library

via the internet. But a more important photograph of William Dobell at

an Awaba children’s summer camp during the mid-1950s, taken with my Box

Brownie, is only available in my personal scrapbook. Anomalies of

significance are no doubt echoed around the country.

Managing personal

information employs established principles, processes, values, skills

and tools as new products arrive for organising, analysing, evaluating,

conveying and securing information and using them to collaborating with

others.

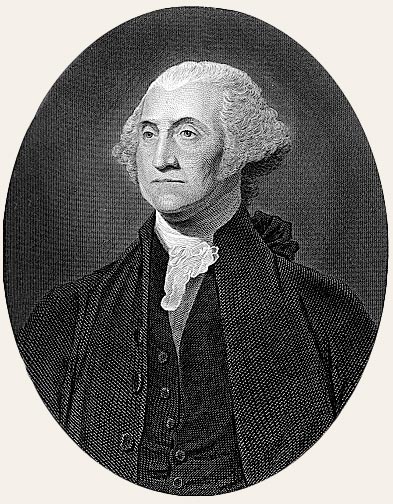

|

| George Washington from Archiving

Early America www.earlyamerica.com |

The methodical George

Washington kept, from the age of fourteen, every scrap of paper

belonging to him and carefully arranged and preserved them. Washington’s

life, says Paul Johnson, is the best documented of any spent in the

entire eighteen century, anywhere.[16]

Two centuries later, it still comes down to method and tools. Few of us

are as organised as Washington. Technology helps us to think

structurally. But it also encourages sloppy methods.

William Jones has

written that, at the centre of method, is making a decision about what

to keep, but making such a decision is fundamentally difficult to do.

Too much information can be nearly as bad as too little information. He

observed that although we are nearing the limits of what can be done to

reduce the costs of keeping, we have only just begun to explore the

potential to reduce the likelihood of keeping mistakes.[17]

As Richard Nixon and Godwin Grech discovered, keeping too much

information can lead to unexpected disaster.

Catherine Marshall says

we flirt with digital brinkmanship. Digital loss has a tendency to be an

all-or-nothing proposition. People don't lose just a few of the baby

pictures of their first child; they lose all of them. She calls

for a radical revision of the way we approach personal digital

archiving. We need to question casual assumptions about the security and

accessibility of information stored in the cloud. We need a combination

of services and mechanisms that will make it possible to designate which

of our digital things are the most valuable. We need to organise the

rest of them into tractable archives that reflect the value of items and

to not spend all kinds of extra time taking care of them. While it is

seductive to envision a single venue – storage in the cloud – “it is

more important to know what we have and where we've put it than it is to

centralize all of our stuff into a single repository.”[18]

Individuals

in organisations

Old notions about

public information are changing.

The Australian

Government 2.0 Taskforce report and a series of supplementary reports

published in 2009 examine the potential use of Web 2.0 technologies by

governments, and by extension, other sorts of organisations. Its broad

recommendations emphasise leadership, policy and governance to achieve

shifts in public sector culture and practice, the application of web 2.0

collaborative tools and practices, and greater open access to public

sector information. This approach will “make democracy more

participatory and informed, improve the quality and responsiveness of

services, deliver services with greater agility and efficiency, unlock

the economic and social value of information as a precompetitive

platform for innovation, and make government policies and services more

responsive to people’s needs and concerns."[19].

Some of the supporting

documents contain analysis to tempt a devil’s advocate.

Economic arguments for

implementing change point to existing poor information management

practices and to the potential for increased productivity. Professor

John Quiggin, one of the project’s authors, observes that most

Australian cultural institutions, including libraries, archives and

museum, have implemented digitisation strategies as ‘unfunded mandates’,

and in the face of budget constraints, most have opted for some form of

cost recovery, despite the potential for greater social benefit from a

free, publicly financed approach. Our devil’s advocate might quibble

with this if he has a different view on priorities for taxpayer-funded

programs.

On the preservation of

Web 2.0 content, the report urged a more expansive view of information

management, clearer guidelines for capturing appropriate records from

social media, and further exploration of recordkeeping in crowd-sourcing

projects and engaging with the cloud. In supporting the proposition that

more prominence be given to metadata, it pleaded for a ‘layered

approach’ to make up for the lack of comprehensive metadata and for

simpler metadata sets to overcome what it calls “metadata paralysis”. It

also pointed to past recordkeeping failures and it lays some blame at a

“lack of leadership by information management professionals in

remedying” these failures.

In assessing the

report’s observations, our devil’s advocate might ask whether “metadata

paralysis” is real or imagined. He might ask whether “simpler metadata

sets” are less important than the application of more rigorous

vocabularies. And he might question whether information management

professionals are inhibited not so much by their attributes as by other

factors. The records management business is more about being methodical

than taking great risks. Most information professionals, including

record managers, will find leadership a difficult call because, as

middle managers, they dance to someone else’s tune. In public sector

circles, responsibility lies with the CEO.

The taskforce chairman,

Nicholas Gruen, in a separate piece about the report, highlighted recent

engagement with Web 2.0 opportunities outside the public sector. Firms

are successfully adapting aspects of volunteerism to their own

organisational structure, policy formulation, and bureaucratic

processes. Formal status is not as important as it was in the past.

Google and the software maker Atlassian allow employees to spend one day

a week on projects that may bring benefits to the firm. The workers are

free to choose. However, although greater recognition of volunteer

contributions can create many organic possibilities and unexpected

associations, there are productivity questions. Introducing ‘Google

time’ by edict into the public service may reduce productivity. The

Taskforce report therefore has recommended an incremental approach in

encouraging staff to experiment and enhance their agencies’ worth.[20]

Responses by cultural heritage institutions

Libraries, archives and museums, if we

discount policies and legislation relating to digital recordkeeping by

governments, have been gnawing at the problem of dealing with digital

lives for the best part of a decade. What are some of the efforts that

attempt to advance solutions?

In the United Kingdom

Personal Archives

Accessible in Digital Media (PARADIGM) was a JISC-funded project by the

university libraries of Oxford and Manchester. It reviewed selected the

practices of working politicians in the search of ways to harmonise

acquisition of digital personal archives with traditional archival

processes.[21]

The project report,

published in March 2007, makes recommendations revolving around

development of roles, skills, standards, and more effective engagement

with creators of records. The project workbook has sections on

collection development, working with record creators, appraisal and

disposal, administrative and preservation metadata, arranging and

cataloguing digital and hybrid archives, digital repositories, digital

preservation strategies, and legal issues. The appendices include a

number of useful tools include a model gift agreement, guidelines for

creators of personal archives, creating screenshots, capturing directory

structures, harvesting websites with Adobe Acrobat Professional 7.0,

exporting email from Microsoft Outlook email clients and other useful

information.

The Digital Lives

Research Project, set up at the end of 2007 with funds from the Arts and

Humanities Research Council, brought together staff from the British

Library, University College London and University of Bristol, under the

leadership of Dr Jeremy Leighton John.[22]

To address the paucity

of research in this area, the project posed a series of questions to

guide its work on personal digital collections. What are the

implications of digital obsolescence and ephemeral media for the

transfer of personal digital collections from individuals to long-term

repositories? Do we need to be more pro-active? Can we develop better

guidance, toolkits and services for individuals to ensure preservation

before transfer? Should we explore methods for continuous capture of

collections over individual lifetimes? How should we address hybrid

personal collections of digital and traditional media? Are there new

organisations acting as intermediaries for managing and publishing

personal digital collections?

The project held an

international conference at the British Library in February 2009. It

published a discussion paper by Andrew Charlesworth on the legal and

ethical issues in October 2009. A final report, initially due in June

2009, and was published in February 2010, after this article was

written.[23].

In lieu of the report, the following commentary draws on recent articles

and presentations by Jeremy Leighton John and other project personal.

In an article published

in April 2008, reporting the findings of interviews with creators of

personal digital personal collections, John and his colleagues

highlighted the high risk of losing “whole swathes of personal, family

and cultural memory.” Previous research relating to personal information

management, they noted, had been fragmented by application and device.

It has focussed on email, the internet and paper of electronic retrieval

rather than broader issues.[24]

Personal practices associated with

managing personal digital archives are extremely complex, they said, and

few patterns had emerged from the interviews conducted during the

initial stages of the project. There were significant differences in

methods and places of storage, familiarity and expertise with hardware

and software. There were widespread differences in perceptions about the

meaning of personal digital collections and about issues surrounding

their preservation. There was widespread misunderstanding about what is

created or stored online and what is created or stored offline,

particularly email. Some respondents did not know whether their messages

were stored on their own computer or remotely. There was also ambiguity

about the meaning of ‘back-up’, ‘storage’ and ‘archive’. There were a

number of questions to be explored in the remaining term of the project.

What do people want and expect to happen to their digital collections at

the end of their lives? What motivates people to share digital files

during their lives? And which types of files do individuals share (and

not share but retain) and in what circumstances?

For curators and archivists, there is

unlikely to be a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to personal digital

collections. It will be important for to be able to deal with and advise

on multiple storage media and file formats. Recordkeeping tools may be

helpful providing they offer flexibility in supporting individual

requirements. Educating the creators of digital records on a range of

issues will be needed.

In Adapting Existing

Technologies for Digitally Archiving Personal Lives, John examined

technical issues around the transfer of information on superseded media

to new media. He explored the use of software and hardware from the

forensic, ancestral computer and bioinformatic communities – such as

Forensic Toolkit, Macintosh Forensic Suite, Back Track, Coroner’s

Toolkit and many other applications. It is essential, he said, that we

not to rely on any single technology for digital capture and to continue

the process of exploring, adopting and adapting this technology.[25]

And in

another more recent article, he and others working on the project, after

acknowledging that little is still known about what people do and why

they do it, explored a information lifecycle approach.[26]

In the United States

The OCLC Online

Computer Library Consortium’s project, Sharing and Aggregating Social

Metadata, focuses on the cloud. Features of social media sites under its

scrutiny include the use of tags, controlled vocabularies, comments,

annotation and reviews, ratings, lists, images and video, articles,

links, filtering, and policies. Under the leadership of Karen

Smith-Yoshimura, the project includes representatives from universities,

public libraries, museums and historical societies, including Rose

Holley from the National Library of Australia. Aspects being explored

revolve around site objectives, measures of success, best practices,

moderation, and attempts by cultural institutions to integrate social

metadata into formal taxonomies. A report is anticipated in early 2010.

Smith-Yoshimura, in

presentations about the project at the RLG Partners Annual Meeting in

June 2009 and the OCLC Digital West Forum in September 2009 offered

preliminary observations on work already undertaken.[27].

There are a great variety of sites. Success appears to be tied to the

objective and the type of audience, not necessarily traffic. They appear

to be of value in leveraging a “sense of community.” Some sites are

heavily moderated, others are not moderated. Institution-specific sites

have fewer contributions than aggregate sites. Tags contributed at

network level are of more value. Tagging is most useful when there is no

existing metadata. Success depends on a critical mass and a sense of

community. Some promising areas include the use of sites like Flickr to

identify “mystery photos” and provide context, CommentPress for

translating, transcribing digitised documents in different languages and

scripts, and the integration of user corrections, as used in Flickr

commons, Minnesota Historical Society’s WOTR (Write on the Record) site,

and the UK National Archives site, Your Archives.

The list of social

metadata sites being reviewed by the working group can be viewed at

http://oclcresearch.webjunction.org/social_metadata. Among the sites

are prominent services like Amazon, Flickr Commons and Wikepedia.

International library, archive and museum sites and projects include the

British Library’s Archival Sound Recordings, Netherlands Institute for

Sound and Vision, Polar Bear Expedition Digital Collections, Science

Museum of Minnesota’s Science Buzz, The Social OPAC, Steve (the Museum

Social Tagging Project), Ancestry’s World Archives Project, and WorldCat.

Australian and New Zealand sites include Archives New Zealand Audio

Visual Wiki, the National Library of Australia’s Argus Index 1870-1879,

Auckland War Memorial Museum’s Cenotaph Database, the Australian

Newspapers beta, Historic Australian Newspapers, 1803-1954, Digital NZ,

Mariners and Ships in Australian Waters of State Records NSW, Auckland

Museum’s Memory Maker site, Picture Australia, the Powerhouse Museum,

and State Library of Queensland.

In addition to these

sites, investigators of the subject may be interested in Archives

Outside (http://archivesoutside.records.nsw.gov.au/),

Now and Then (http://www.nowandthen.net.au/), a site that gathers

material about the small South Australian township of Mallala, and

Museum of Victoria’s site, Collectish (http://www.collectish.com/).

In July 2009, the

Library of Congress National Digital Information Infrastructure and

Preservation Program launched a pilot program to test cloud technologies

for preserving digital content. The pilot will focus on a new service,

DuraCloud, to be developed and hosted by the DuraSpace Foundation. The

New York Public Library and the Biodiversity Heritage Library are among

participants. The test will cover both storage and access services,

including services that span multiple cloud- storage providers. The

program will focus on providing trusted solutions for organisations such

as universities, libraries, cultural heritage organisations, research

centres and others who are concerned with ensuring perpetual access to

their digital content.[28]

In February 2010, the

Internet Archive organised a conference on personal archiving and has

established a website at

http://www.personalarchiving.com/ to attract further conversations

on the subject.

In Australia

Another Australian site

listed by OCLC Group is the Community Created Content Project of

National and State Libraries Australasia (NSLA),[29])[29],

a project in NSLA’s strategic plan Re-imagining Libraries, with

programs relating to e-resources, virtual reference, document supply,

new work environments, collaborative collecting, collection management,

economic issues, and metadata. The Community Created Content project

sets out to develop a sustainable framework for individuals and

communities to build personalised digital library spaces where they can

create, tag and protect content and share it with family, peers and

groups and feeding that content into community, institutional and

preservation repositories.

As an initial step Paul

Reynolds, Adjunct Director of the National Library of New Zealand and

Managing Director of Mcgovern online media, has produced the discussion

paper NSLA Project Five: the Project @ April. This proposed a set

of online tools and web services designed to leverage knowledge assets

within the web ecology by enabling the assembly of personalised library

customer web spaces and sharing information in these spaces.

These tools consist of

four stations. The first, a source station, will give users the ability

“to manage, store, subscribe and direct their own ecology of web

information and web sources.” The second, a search station will deliver

“search and discovery features based on customised user profiles to

allow them to search and retrieve the rich set of sources available from

the open and subscription-based deep web.” The third, a social station,

will give every library user in Australia and New Zealand a social

networking space which will offer the ability “to participate in a rich

collaborative digital public space that can be shared with other social

networking spaces”. And, the fourth, a remix station, will give the user

“the ability to create a personalised user/group creative studio where

the user uploads, co-creates, shares and remixes to the world.”

NSLA is currently

working on a presentation tool to assist in building a community of

practice relating to the project, establishing a web space and

development of the toolkit. Resourcing requirements will be submitted to

the NSLA members for endorsement at the NSLA meeting in March 2010.

Other international deliberations

At the RLG Partnership

Annual Meeting in June 2009, several presentations caught my eye for

their relevance in dealing with personal digital collections and

activity in the cloud. Karen Smith-Yoshimura and Thomas Hickey, in

Names and Identities, reported on the Networking Names Advisory

Group’s work on a cooperative identities hub and framework “to

concatenate all forms of names using a social networking model. Hickey

and Ed O'Neill spoke about the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF),

a service to provide free access to the world's major authority files,

as one of the building blocks for the Semantic Web. Penny Carnaby

(National Library of New Zealand), in Going Global, flagged

possible changes to roles when outlining how national libraries can work

together with academic libraries, archives and museums. And Diane

Vixine-Goetx spoke about OCLC’s Terminology Services, which aims to make

the terms and relationship in controlled vocabularies available as Web

resources.

At OCLC Digital Forum

West in September 2009, Jonathan Furner, in Twenty Tall Tales About

Tagging, questioned widespread views about tagging, a field of

enquiry that tends to be based on opinion rather than evidence. Anne

Gilliland, in Increasing Digital Discovery and Delivery, urged us

to make more out of metadata, including the use of expert-created

metadata. And Luis Mendes, in Out of the Mouths of Users into

Library Systems, put the case for the continued develop of tags and

controlled vocabularies as complementary systems.

Additional issues have

been exposed in other recent conferences. From the IPRES Conference in

October 2009, Jens Ludwig’s Into the Archive: Potential and Limits of

Standardizing the Ingest, deals with the complexity of ingesting

digital material, work underway, and possible future steps. Maureen

Pennock’s ArchivePress: A Really Simple Solution to Archiving Blog

Content provides an update on research by British institutions on

significant properties of blogs and the development of related open

source plug-ins. Johanna Smith and Pam Armstrong (Library and Archives

Canada) talked about the influence and collaboration with record

creators in preserving the digital memory of the Government of Canada in

Are you ready?[30]

The DigCCurr 2009

conference, part of a three-year project funded by the Institute of

Museum and Library Services, focussed on the need to improve graduate

level programs for professional training in digital curation.[31]One

of the presenters, Andreas Rauber demonstrated HOPPLA (Home and Office

Painless Persistent Long-term Archiving), which is under development at

the University of Technology Vienna. This system will offer back-up and

automated migration services in personal data collections and SOHO (Solo

Office Home Office) settings. The project is exploring system design

requirements and professional development needs.[32]

Summing

up

Social media are like

other media. Quality floats on a sea of dross. However, as George

Steiner observed, many tongues are better than one voice.