|

|

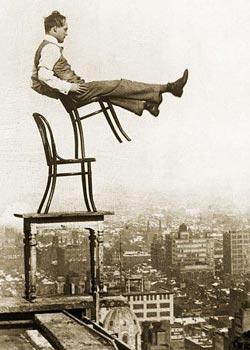

Source: http://jeannevb.com/on-the-edge |

The

slogan for the 17th ALIA Information Online

conference was At the Edge. As delegates

travelled up the escalator towards the opening plenary

session, they left behind a world in which the use of

technology has produced tensions.

Chelsea Manning, Julian Assange and Edward Snowden were

holed up because they believed the world had become too

much like Nineteen Eighty Four. Social media that

four years ago had been used to inspire hope in Tunisia

and Egypt were now being used by Islamic State as

a black art to terrorise the rest of the world. How

close to the edge would the conference take those

assembled in the comfort of the Sydney Hilton Hotel? And

what sort of a difference would it make to what they do

tomorrow? [1]

THE TALK AT THE

CONFERENCE

The big opportunity

Siva Vaidhyanathan urged libraries to occupy land that

Google is now leaving. Drawing on his book

The Googlization of Everything and Why We Should Worry, the

Professor of Media Studies at the University of Virginia

said Google had begun to solve what used to be regarded

as a library problem. Their search engine invention had

sucked all the energy out of the room and forced

libraries to become defensive. But Google is no longer

the same company. It now wants to be the operating

system of our lives, to be responsive to the flows of

data controlling the operation of fridges and cars. Book

scanning and similar initiatives have been “parked on

the side.”

To help libraries seize the

day, he proposed a Human Knowledge Project, modelled on

the Human Genome Project, as a networked digital

collection of collections.[2] The dream of universal

access to comprehensive knowledge, he said, is not new.

But is what we have already done the best we can do?

We’ve long had the technology. What we have lacked is

the political will. The Human Knowledge Project is a

concept for investing in technology, people and

buildings to create national networks with local and

global impacts. Citing Diderot’s

Encyclopédie

as one of

the antecedents of such a project, he said the Digital

Public Library of America, the Internet Archive and

Trove are potential partners among a wider range of

stakeholders.

Remaking library spaces and

services

Erik Boekesteijn’s

message was that extreme library makeovers and mind

shifts are needed in order to survive. As director of Doklab

(http://www.doklab.nl/en/), a consulting service in

concept and product development located at the Delft

Public Library, he keeps his finger on the pulse through

the Shanachie Tour (http://www.shanachietour.com/),

highlighting the work of libraries around the world, and

a weekly online talk show, This Week in Libraries.

(http://www.thisweekinlibraries.com/). His slide show

offered a smorgasbord of mind shifts from his travels

and shows. These include digital signage, transit

screens, learning labs, makerspaces, rooms for hire, use

of social media, smart use of library cards, managing

user-generated content, e-publications and slippery dips

from one floor to another. Initiatives worthy of

attention include the Singapore Memory Portal (http://www.singaporememory.sg/)

and the digital library on the walls of a Bucharest

subway station.[3] Libraries, he said, need to become

the starting point for a conversation. In the end, it is

how libraries make people feel that is important.

Liz McGettigan gave a

lesson in attitude. The Director of Digital at SOLUS UK

called for radical transformation to deliver

customer-centric services in hi-tech libraries.

Libraries have responded well to emerging challenges,

she said, but they still feel threatened. Drawing on her

experience as Head of Libraries and Information Service

for the City of Edinburgh, she reeled off pragmatic ways

to manage and sell services. Librarians need to be

opportunistic, take the lead, demonstrate energy, know

their strengths and be prepared to make mistakes. They

need to make changes within existing budgets and do

something different every year. And, in a Scottish burr

worthy of Mel Gibson’s call to his kilted highlanders in

the film Braveheart, she urged those assembled on the

battlefield to “choose glory”.

Planning tools and

techniques were explored by a number of speakers. Sue

Hutley (Queensland University of Technology) homed in on

the value of trends as a starting point. After citing a

number of sources worthy of study, she focused on the

2014 Horizon library trends report and the blips on its

radar screen -- changing research environments, mobile

content and delivery, developments in standards and

infrastructure, electronic publishing, the Internet of

Things, the Semantic Web and linked data.[4] Two

presentations highlighted the value of design thinking

(Rebecca Goldsworthy and Kate Masters from the

University of Sydney Library and Justine Hyde, Ben

Conyers and Bridie Flynn from the State Library of

Victoria). Alison Pepper and Margie Janttl described the

development of the University of Woollongong’s ‘value

cube’ database, which has been used to learn more about

student borrowing and online resource usage patterns.

Jennifer Crosby and Kimberley Williams (University of

Technology Sydney) championed the creation of a 'sticky

campus' to encourage staff and students to become

involved in the planning process.

Government and business libraries are often the most

vulnerable in volatile times. Kim Sherwin (Arup) and Pia

Waugh (Australian Department of Finance) offered their

experience of going on the front foot. Two librarians

were generous enough to expose the raw side. Laura

Atkinson’s experience was leading restructuring of

Victorian Government libraries, where 55 libraries were

reduced to 19 services and 14 locations were reduced to

3. On the plus side, the changes have led to greater

consistency in service delivery and more direct online

access to resources. But her final comment - “Don’t

trust anyone”- exposed the emotional side of the

process. Cynthia Love was called upon to respond to

funding pressures by making extensive changes to

information services at the CSIRO. With full online

service delivery by 2016 as the goal, this has involved

consolidating collections, weeding duplicated and

obsolete material, establishing a single document supply

centre, adding data management responsibilities, and

assigning librarians to strategic research projects.

Being in step with the organisation is important. But

sometimes there is no rational explanation for what you

are asked to do.

Public library

developments of the kind highlighted by Erik Boekesteijn

were picked up in local case studies. Tania Barry’s work

at Hume Libraries in Victoria has involved the

establishment of a makerspace, equipped with

technologies for content creation, programming and 3D

printing. Lisa Miller gave us a picture of the new media

lab at City of Gold Coast Libraries’ Helensvale Branch,

which has attracted new users and forged links with

small businesses. Measuring the success of the venture,

she said, has been difficult, but success of ventures

like this, like the success of exposing children to

books, is surely best measured years down the track.

Discovery, digital creation and digitisation

Mitchell Whitelaw, from

the Centre for Creative and Cultural Research at the

University of Canberra, reprised and updated his keynote

address about generous digital interfaces at the 2013

ALIA Biennial conference. Further experiments are

exposing new ways to enrich collections, locate items,

and understand subjects. They are drawing attention to

the value of serendipity, challenging notions of

significance and posing questions about the allocation

of budgets on solutions for searching and browsing. The

work of the Internet Archives, for example, in adding

2.6 million tagged images with OCR text from scanned

books was achieved at minimal cost by one person using a

computer. An improved understanding of authors in the

Bloodaxe archive of contemporary poetry at Newcastle

University in the UK was engineered by using a

marginalia machine and linking data to the British

National Bibliography. Spotify’s Every Noise at Once, a

map of music genres, makes it possible to drill down on

recordings in specific genres and explore related genres

in the music streaming service. The tranScriptorum

project is developing solutions for indexing, searching

and transcribing historical handwritten document images.

As a takeaway article, he recommended Alexis Madrigal’s

article How Netflix Reverse Engineered Hollywood, about

the creation of a new genre generator.[5]

Sarah Kenderdine, Deputy

Director of the National Institute for Experimental Arts

and Director of the Laboratory for Innovation in

Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums University of

NSW (iGLAM Lab), encouraged institutions to take on a

role as “applied laboratories and nodes of

experimentation for the cultural imaginary of our times”

by using new media art practice to create immersive

experiences, interactive cinema, augmented reality and

embodied narratives -- creating experiences for which

there has been no former demand. From her portfolio she

offered some enticing examples, undertaken mainly in

partnership with the museums and heritage sites:

mARChive (Museum Victoria’s data browser for 100,000

objects in 360-degree 3D); Look up Bombay (a gigapixel

dome work for the Prince of Wales Museum, Mumbai);

Pirates Scroll 360 and Pirates Scroll Navigator (two

treatments of a scroll painting, Hong Kong Maritime

Museum); Pure Land: Inside the Mogao Grottoes at

Dunhuang and Pure Land Augmented Reality Edition (based

on interactive facsimiles of the World Heritage site, Dunhuang, China);

Kaladham (based on the World Heritage

Site, Hampi, India) and ECloud WW1 (a world touring

exhibition representing 70,000 objects in 3D from the Europeana website). Projects in the pipeline for major

museums in Australia are devoted to a hospital operating

theatre, Asia and Aboriginal culture. Her takeaway

citation was an article in The Atlantic which posed the

question: what is a thing?[6]

Three presentations about

Trove, tucked away in the concurrent sessions, deserved

greater prominence because of the important messages

they conveyed.

The first message was

that Trove, despite its success, is done on the cheap.

The National Library of Australia’s Marie-Louise Ayres

compared the Australian discovery services with similar

enterprises around the world – Europeana, DigitalNZ and

the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) – to

highlight progress and opportunities. Although they have

similar purposes, they have completely different

government mandates, governance frameworks and funding

dimensions. Trove’s content base is much more diverse

and complex than the others. Trove and DigitalNZ offer

workmanlike search interfaces compared with the more

arresting design features of Europeana and DPLA. All

services have an open access agenda, but Trove is

hindered in delivering this goal by complexities around

licensing, metadata, and other matters. Trove is also

hampered by the fact that it doesn’t have a clear

Government mandate and major funding outside the

National Library’s budget. It can only develop things

incrementally and its capacity to assist prospective

contributors is limited. Only time will tell whether the

next five years will bring further convergence or

further divergence and whether new players will change

the aggregator environment in ways not yet imaginable.

The second message was

that Trove is great, but it isn’t perfect. Trove

Manager, Tim Sherratt, challenged the notion that a

‘seamless’ world of information is possible. As we

imagine the future of a service such as Trove, how do we

balance the benefits of consistency, coordination and

centralisation against the reality of a fragmented,

unequal, and fundamentally broken world? Trove is an

aggregator and a community, a collection of metadata and

a platform for engagement. In exploring possibilities,

we need to acknowledge its limitations. It is not

perfect. It is not everything. It is not a machine.

Although library services cannot compete with Google’s

oracular power, they can strive to offer users a

comparable level of simplicity. And, by exposing

assumptions and imperfections, collection gaps and

strengths, data visualisation techniques can reveal ways

to educate the public, analyse data and repair what

appears to be broken.

The third message was

that Trove has paved the way for harvesting data from

types of contributors who were once excluded. Julia

Hickie and Mark Raadgever drilled down on the work of

the harvesting of content from the Australian

Broadcasting Corporation’s Radio National (RN) website

as a way of expanding Trove’s news coverage. This

involved devising non-standard systems and protocols to

capture 84 separate RN programs using Sitemaps, checking

RN RSS feeds and converting metadata to Dublin Core, a

workaround that, in partnership with the ABC, has

produced an alternative to the Open Archives Initiative

Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH). It has been

effort that has enabled the library to bring content in

from a number of other data sources, such as the

Australian Government Solicitor’s Legal Opinions

website, the Australian Parliamentary Library’s Press

Releases database and the AusStage events database. It

will make it possible to extend collaborations to owners

of content management system websites. The library is

“taking its blinkers off and thinking beyond

conventional data types and content partners.”

Maggie Patton shone a

spotlight on digitisation programs at the State Library

of New South Wales, which in 2012 was the beneficiary of

a commitment of $48.6 million by the NSW Government for

the initial five years of a ten year program. This has

enabled infrastructure and systems renewal, involving

the acquisition of Ex Libris products, Rosetta digital

asset management system, and Axiell Group’s Adlib

Archive among other systems. Over the past 2 years, 1.3

million pages or approximately 4,500 books from the

extensive David Scott Mitchell printed book collection

have been generated, over 2.6 million newspaper pages

have been released through Trove, and over 180,000 pages

from the Library’s extensive WWI diary collection have

been digitised. Other elements of the program include

contributions to Flickr Commons, Wikipedia and Google

Cultural Institute, the use of a transcription tool to

assist volunteer transcribers, geo-referencing its

cartographic collections, and open data initiatives. In

other papers, Adrian Bowen explored the digitisation of

the oral history collection at the State Library of

Western Australia, where protocols have been adopted to

deal with orphan works. Dianne Velasquez and Jennifer

Campbell-Meier touched on the digitisation in

information repositories and other forms of digital

collections in the the university sector.

Do libraries still need

to invest in the web-scale discovery services such like

Primo, Summon, EDS and WorldCat Discovery Services? This

was a question tackled from library and vendor

perspectives. Andrew Wells (University of New South

Wales) drew upon local and American surveys that reveal

changing user preferences for search engines, external

content providers and library systems in universities.

As the move from print to 24/7 online access replaces

the model based on ownership of physical resources, the

UNSW Library believes its investment on web-scale

discovery systems is currently worth the expenditure.

Bruce Heterick from JSTOR gave a vendor perspective.

There is an assumption that libraries, content

providers, and web-scale discover service providers have

goals that are aligned. Most content providers are

interested in getting content on their platform to as

many users as possible, but need to recover their

significant financial investment. Libraries, too, need

to increase their own level of investment to manage the

changing environment.

Specialised system developments were explored by Clare

McKenzie, Emma McLean, Kate Byrne and Susan Lafferty

from the University of NSW, where a new research output

system, based on Symplectic’s Elements software, has

involved a transfer of responsibilities to academic and

research staff. Katrina McAlpine and Lisa McIntosh gave

details of an eResearch framework at the University of

Wollongong Library to define support services for the

registration, storage, description and discoverability

of research datasets. Cathy Jilovsky and Michael

Robinson described CAVAL’s new D2D (Discovery to

Delivery) service, which streamlines the delivery of

requested resources with minimum mediation. A case study

offered by Maureen Sullivan and Suzanne Bailey was

devoted to Griffith University’s ePress library-based

electronic publishing service. Cecile Paris talked about

work at CSIRO on the development of systems for

searching, capturing, and analysing digital content.

Jane Angel gave a run-down on the delivery of electronic

resources using a rebadged EBSCO Discovery Services at

the Defence Science and Technology Organisation. Clare

Thorpe described how the Identity Management Project at

the State Library of Queensland was streamlining 19

client management systems to make it simpler for users

to gain state-wide access collections and services,

loans, online databases and newsletter subscriptions.

And two speakers -- Trish Hepworth and Thomas Joyce –

talked about fair use copyright reform and approaches

for staying out of trouble.

Connecting with users

The use of social media

is widespread. The State Library of NSW – in papers and

workshops by Mylee Joseph, Kirsten Thorpe, and Ellen

Forsyth – offered the benefit of their experience by

talking about the risks involved, use of the Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Library, Information and

Resource Network protocols when engaging with Indigenous

communities, and ways of measuring the effectiveness and

impact of social media. Richard Gray and Amy Baker, from

UNSW Australia, and Jill Benn, Katie Mills and Roz

Howard from the University of Western Australia,

contributed to sessions on the value of social media in

a university setting. Two presentations -- one by Ozge

Sevindik-Alkan, the other by Alyson Dalby, Amy Barker,

Kate Byrne and Clare McKenzie -- explored the use of

social media and groupware for mentoring and

professional networking. Louise Prichard and Louise

Tegart described how the State Library of NSW was

connecting to exhibition visitors using the Curio mobile

app, which involved a partnership with Art Processors,

developers of the mobile guide for the Museum of Old and

New Art in Hobart.

Digital literacy programs

are being tweaked. Sharon Bryan, Helen Hooper and

Bronwyn Mathiesen focused on the use of games to create

a suite of reusable learning objects at James Cook

University Library. Two speakers -- Bronwen Forster

(Cook University) and Christine Oughtred (Deakin

University) – outlined ways in which library courses

have been developed in collaboration with teachers and

staff. Emily Rutherford, Dr Katharina Freund, Heather

Jenks, Inger Mewburn examined the use of badges to

provide verified credentials to students at the

Australian National University Library.

Collaboration

Troy Brown urged more

collaboration by galleries, libraries, archives and

museums. The GLAM sector currently spends approximately

$2.5 billion, around 80% of which is provided by

government. The GLAM Innovation Study, undertaken by

CSIRO with the Australian Centre for Broadband

Innovation and Smart Services Co-operative Research

Centre as part of its digital productivity flagship

research, reports that their combined collections

contain over 100 million objects, 25% of which is

digitised. Among other recommendations, it proposed a

national framework for collaboration, supported by a

leadership forum, involving “some minimal, cross-sector

governance arrangements beyond the existing professional

and industry associations."[7]

Rebecca Daly and Susan Jones gave an example of modest

cross-sectoral collaboration in their presentation on a

project involving the University of Wollongong Library,

Illawarra Historical Society & Illawarra Museum to pull

together local archival content for digitisation and

online access, including then-and-now streetscape

images, estate and subdivision plans, land title deeds,

historical publications and photographs. A workshop

presentation by Jane Cowell and Ian Wedlock on the State

Library of Queensland’s The Next Horizon: Vision 2017,

which aims to transform Queensland’s 340 public

libraries into physical and digital hubs to capture the

unique histories and contemporary stories in regional

Queensland libraries, museums and historical

societies.[8]

IMPRESSIONS AND REFLECTIONS

The conference left two impressions

that have prompted further reflection. The first was

that the attendance and the number of exhibitors had

declined markedly since the Information Online heyday.

The second was that the program felt more like an annual

version of the ALIA Biennial Conference. Was this year’s

conference really at the edge? And, at a time when most

libraries are wired up, is the conference facing its

use-by date?

Library directions

Technologically-driven change has

affected and continues to influence the development of

industries and those who work in them. Australia’s

collective know-how -- the knowledge and expertise of

its people – is now valued at $16.7 trillion, with

nearly $615 billion added to the total in 2014.[9]

On the other hand, Australia’s digital economy ranking

is slowly receding rather than advancing, as governments

help or hinder future directions.[10]

Commentators continue to depict the

future of libraries in terms of an evolving revolution.

CNI’s Clifford Lynch says the evolution is carried

forward under the enormous strain of a very complex

system. Many institutions are no longer economically

sustainable or stable. Transitions of stewardship

responsibility from one organisation to another will

become increasingly commonplace.[11]

It will be necessary to develop strategies and

infrastructure to deal with these demands effectively,

affordably, and at the requisite scale.[12].

Lorcan Dempsey, OCLC’s chief

strategist and manager of research, also pinpoints the

network as the main driver of the evolution. In The

Network Reshapes the Library, a compilation of his

blogs of the past 12 years, he reflects on the move by

libraries into an evolving ecosystem of information

services. Libraries need to structure their systems,

data, and access protocols to facilitate networked

access across regional collectives, countries and the

world. A lot of habits, systems, and functions will

necessarily change for this vision to take root.

Strategic attention to these areas, he writes, is often

emergent rather than deliberate and issues are

not always pulled together in a single planning

context.[13].

In his OCLC report

Collection Directions: Some Reflections on the Future of

Library Collections and Collecting,

written with Constance Malpas and Brian Lavoie, he

amplifies how the network is reconfiguring libraries

within institutions and across the sector. As libraries

become more engaged in research and learning workflows,

they need to rebalance investment in “commodity”

materials and increase operational efficiencies. An

“inside-out orientation” will become more important as

universities focus on distinctive institutional assets

and libraries direct increased curatorial attention

toward special collections, new scholarly products,

research preprints, and learning resources. Ultimately,

the degree to which these broad environmental changes

will affect academic libraries will depend upon the

availability of appropriate collaborative infrastructure

above the institution. Building shared services at scale

is necessary and a challenge.[14]

Meanwhile libraries and their

suppliers beaver away on systems and standards. Marshal

Breeding, in his annual review of the library systems

marketplace, writes about a relentless consolidation of

systems in the last 12 months, with among issues ongoing

interest in linked data and the development of BIBFRAME

as a replacement for MARC.[15]

Ted Fons, at the CNI December 2014 meeting,

sketched out efforts by OCLC to move away from

inventory-based discovery systems towards linked data

entities and relationships in diverse information

ecosystems.[16]

Dean Krafft and Tom Cramer, in the same meeting,

reported progress in a linked open data project of

Harvard, Cornell and Stanford universities libraries,

which aims to produce an ontology, architecture, and set

of tools that will work within and across individual

institutions in an extensible network.[17]

And Jerome McDonough, in Falling Though the Cracks,

expressed the hope that libraries, archives and

museums will use linked data and other standards to

capture intangible heritage information and overcome the

inertia around cooperative collection development.[18]

In March 2015, the National

Information Standards Organization launched three new

projects to develop new standards to better support

exchange and interoperability of bibliographic data'[19].

Library associations and conferences

Since the first library association

was launched at the Pennsylvania Historical Society

conference in 1876, their number and nature have

expanded globally around general and specialist

interests. Their conferences are usually pitched as

professional development and networking opportunities

rather than as forums for advancing big ideas in

concert.

The first Information Online

conference was presented in January 1986 under the

management of ALIA’s Information Online Group.[20].

The reins have now been transferred to the ALIA head

office and the number of delegates and exhibitors has

declined in recent years. Melbourne interests in

libraries and technology preceded those in Sydney. The

independent Victorian Association for Library Automation

(http://www.vala.org.au/), established

in 1978 and now rebadged as

Libraries,

Technology and the Future Inc, organised its

first conference in 1981. The roll-up to the biennial

Melbourne conferences matches the attendance at the

biennial Sydney conference.

The Australian Library and

Information Association, in addition to organising the

Information Online conference, also now hosts three

other national conferences -- the ALIA Biennial

Conference, the New Librarians Symposium, and a National

Library and Information Technicians’ Symposium.

Specialist conferences devoted to

online information and technology abound here and

overseas. Their papers, slides and videoed presentations

are generally made available via conference websites or

video channels.

Is this the best we can do?

The Information Online conferences

have resounded with the catch-cries of computing,

content, connectivity and customers since the

Information Online conferences began. This one was no

exception. Every conference needs an agent

provocateur and the one who stepped up to the plate

at Information Online was Siva Vaidhyanathan, who

challenged libraries to do better in the next phase of

the information revolution. Is it a question of

advocating value or of marshalling forces?

ALIA had used the conference to

launch its new advocacy campaign FAIR (Freedom of Access

to Information Resources) as a way of giving more

prominence to lobbying needed on library funding, legal

deposit, digitisation, evidence-based policy making,

copyright law reform and other matters.[21]

Liz McGettigan, in her

presentation, urged delegates to find a new language for

dealing with funders. Sue Hutley underscored the need to

adopt IT infrastructure and performance standards, an

issue now on the agenda of the Council of Australian

University Librarians. Five years ago,

Marie-Louise

Ayres in a discussion paper to National and State

Libraries Australia commented on the lack of

standardisation of practice and performance across the

libraries NSLA represents.[22]

And we can go as far back as 2001, when John

Houghton, in his report for CAUL, The Economics of

Scholarly Communication, wrote “the library

community does not have a particularly good handle on

its own costs or standard approaches to data collection

on holdings, expenditures, staffing. All too often

judgements are made, rather than decisions, because of a

lack of information.”

Siva Vaidhyanathan

had spoken about Google’s interest in

the Internet of Things, which may affect the future of

libraries but is currently at the outer reaches of their

interest and control.[23]

His call for a Human Knowledge Project

has antecedents in plans by Paul Otlet and Henri-Marie

La Fontaine to create a world index of literature in the

1890s. Knowledge management has lost its gloss in recent

years because of the inherent difficulties of creating

and maintaining trust in a cynical world of rapid

change.

The

GLAM Innovation Study is the latest attempt to

stimulate concerted local action by galleries,

libraries, archives and museums. Drawing people,

processes and technologies out of the GLAM sector silos

has been a major challenge. The experience of the

National Digitisation Information Infrastructure

Preservation Program in the United States highlighted

the difficulty of collaboration in diverse environments.

The closure in 2010 of the Collections Council of

Australia, on which the main GLAM sector bodies were

represented, put the brakes on a momentum that had built

up with the help of government money. Museums Australia,

in consultation with ALIA, has organised a meeting of

GLAM sector bodies in June to take stock of the

situation.

Funding from the three levels of

government funding will undoubtedly be needed to draw

mixed interests and capabilities into a more unified

digital space. But it is worth remembering that ALIA and

Museums Australia both owe their existence to the

substantial support of the Carnegie Corporation in the

1930s. In 2007 the Northern Territory Library received

an award of US$1 million from the Bill and Melinda Gates

Foundation for its work to improve the lives of

Indigenous Australians. International forums such as

APEC and the G20 may provide lessons on ways of

conferring and resolving things that need to be done.

The under-funded Trove initiative is a solid platform

that calls for more imagination, specification and

commitment to build the rest of the house.

There is a case for letting things

evolve. In 2004, the former Deputy Director of the

National Library, Eric Wainwright, in noting the

Australian library sector was without a national body

through which libraries can pool resources to influence

government policy, develop strategy and encourage

cross-sectoral projects, wrote that “most of us have

less belief both in grand visions and the likelihood of

broad consensus.” He argued the need for summit-style

gatherings had changed and the information and

communication fields were so fast-moving that

institutions were having themselves to react more

quickly. It is less likely that national mechanisms

built on consensus can respond within the timescales

needed for decisions. [24]

But, as Clifford Lynch asserts, the era of letting a

thousand flowers bloom may be over and a new phase of

the information revolution may compel more effective

concerted action.[25]

Unless you're optimistic there are reasons to be

pessimistic. Maybe the intelligence that libraries are

seeking to foster is overrated? The public intellectual

Noam Chomsky, in a recent talk about the failure of

humans to deal with nuclear and environmental threats,

claimed that intelligence was a

lethal mutation: lower forms of life such as bacteria

and beetles will survive homo sapiens, whose use-by date

has almost arrived.]26]

The physicist Stephen Hawking has offered the view that

the full development of artificial intelligence

could spell the end of the human race.[27]

Will the robots have arrived by the

next ALIA Information Online in February 2017?

Endnotes

[1] ALIA information

Online Conference 2015 program and papers:

http://information-online.alia.org.au/

[2] Vaidhyanathan S, "The Human Knowledge Project"

paper presentedat the Cultural Policy Centre,

University of Chicago, 29 October 2013

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VtX6J31ZpC8

[3] MDG Advertising. “Bucharest

Subway Station Turned into Digital Library”, MDG

Advertising and Marketing Blog (10 February 2013).

http://www.mdgadvertising.com/blog/bucharest-subway-station-turned-into-digital-library/

[4] Johnson L, Adams Becker S, Estrada V, and

Freeman A, NMC Horizon Report: 2014 Library Edition.

(The New Media Consortium, 2014)

[5] Whitelaw M, "Collection Space" (paper presented at

Information Online Conference 2015, Sydney, 5

February 2015, with links to

experiments mentioned above https://t.co/YIoGrGvXMK);

Madrigal AC, “How Netflix Reverse Engineered

Hollywood”, The Atlantic 2 January 2014

http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/01/how-netflix-reverse-engineered-hollywood/282679/

[6] University of New South Wales National Institute

for Experimental Arts. Professor Sarah Kenderdine:

Biography http://www.niea.unsw.edu.au/people/professor-sarah-kenderdine;

University of New South Wales National Instittute of

Experimental Arts. Laboratory for Innovation in

Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums (iGlam) http://www.niea.unsw.edu.au/research/organisations/laboratory-innovation-galleries-libraries-archives-and-museums-iglam;

and Meyer R, “The Museum of the Future Is Here”, The

Atlantic (20 January 2015),

http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/01/how-to-build-the-museum-of-the-future/384646/

[7] Mansfield T, Winter C, Griffith C, Dockerty A,

Brown T. Innovation Study: Challenges and

Opportunities for Australia’s Galleries, Libraries,

Archives and Museums, (Centre for Broadband

Innovation, CSIRO and Smart Services Co-operative

Research Centre, August 2014)

[8] State Library of Queensland, The New Horizon

:Vision 2017 (2014)

http://www.slq.qld.gov.au/about-us/corporate/publications/planning/vision-2017

[9] Wade M, “Australia's Collective Know-how at an

All-time High”, Sydney Morning Herald (7 March 2015)

http://www.smh.com.au/national/-13x2wr.html

[10] Chakravorti B, Tunnard C, Chaturvedi RS, “Where

the Digital Economy is Moving the Fastest”, Harvard

Business Review (19 February 2015) https://hbr.org/2015/02/where-the-digital-economy-is-moving-the-fastest

[11] Lynch C, "An Evolving Environment: Privacy,

Security, Migration and Stewardship" (Paper

presented at Coalition of Networked Information

Membership Meeting, Washington DC, 8-9 December

2014

http://vimeo.com/114426257.

[12] Lynch C, "Sharing and Preserving Scholarship:

Challenges of Coherence and Scale". (Paper presented

at the Corporation for

Education Network Initiatives in California

Conference, 10 March 2014),

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FfJBcX9--is

[13] Dempsey L, The Network Shapes the Library:

Loran Dempsey on Libraries, Services and Networks, (American Library Association, 2014).

[14] Dempsey L, Maplas C, Lavoie B, "Collection

Directions: Some Reflections on the Future of

Library Collections and Collecting" (2014) 14(3)

portal: Libraries and the Academy 393

http://www.oclc.org/content/dam/research/publications/library/2014/oclcresearch-collection-directions-preprint-2014.pdf

[15] Breeding M, "Library Technology Forecast for

2015 and Beyond" (2014) 34 Computers in Libraries

10 at 22ff. (http://www.infotoday.com/cilmag/dec14/Breeding--Library-Technology-Forecast-for-2015-and-Beyond.shtml).

[16] Cole T, Sarol J, Fons T, and Arlitsch K, "Exposing Library Collections on the Web: Challenges

and Lessons Learned", (Paper presented at Coalition

for Networked Information Membership Meeting Fall,

Washington DC, 8-9 December

2014),

http://youtu.be/WEl0CJPI4DI

[17] Krafft D and Cramer T, "The Linked Data For

Libraries (LD4L) Project: A Progress Report", (Paper

presented at Coalition of Networked Information

Membership Meeting 8-9

December 2014)

http://youtu.be/QYd_OlenZ5U

[18] McDonough J, "Falling Though the Cracks: Digital

Preservation and Institutional Failures", (Paper

presented at Coalition of Networked Information

Membership Meeting 8-9 December 2014)

https://youtu.be/gZy2eC5y3MY

[19] National Information Standards Organisation. Bibliographic Roadmap Development Project,

www.niso.org/topics/tl/BibliographicRoadmap/

[20] Swan E, “Information Online 1985 +: a salute”

(2012) 33 Incite 3

[21] Australian Library and Information Association,

Fair Initiative

http://fair.alia.org.au

[22] Ayres ML, Faster Access to Archival Collection

in NSLA Libraries: Project Report, (National and State Libraries

Australia, 2010)

http://www.nsla.org.au/sites/www.nsla.org.au/files/publications/NSLA.Discussion-Paper-Faster.access.to_.archival.collections_201010.pdf

[23] Online Computer Library Center, “Libraries and the Internet of Things”, Nextspace

(15 February 2015)

http://www.oclc.org/publications/nextspace/articles/issue24/librariesandtheinternetofthings.en.html

[24] Wainright E, “Glory Days? Reflections on the

1988 Australian Libraries Summit and its

Aftermaths”, 2004 53 Australian Library Journal

1.

[25] Lynch C. "Sharing and Preserving Scholarship:

Challenges of Coherence and Scale". (Paper presented

at Corporation for

Education Network Initiatives in California

Conference, March 2014)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FfJBcX9--is

[26] Chomsky N, The Emerging World Order: Its Roots,

Our Legacy, (3 February 2015)

http://youtu.be/6ccNt4Dzyfg

[27] Balkam S, “What Will Happen When the Internet of

Things Becomes Artificially Intelligent?” The

Guardian (21 February 2015) http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/feb/20/internet-of-things-artificially-intelligent-stephen-hawking-spike-jonze

Non-commercial viewing,

copying, printing and/or distribution or reproduction of

this article or any copy or material portion of the

article is permitted on condition that any copy of

material portion thereof must contain copyright notice

referring "Copyright ©2013 Lawbook Co t/a Thomson Legal

& Regulatory Limited." Any commercial use of the article

or any copy or material portion of the article is

strictly prohibited. For commercial use, permission can

be obtained from Lawbook Co, Thomson Legal & Regulatory

Limited, PO Box 3502, Rozelle NSW 2039,

www.thomson.com.au