|

|

Body knowledge in bytes: the health industry gears up for the 21st century

by

Paul Bentley

Article originally published in Online Currents August 2013 and reprinted with kind permission

of

Thomson Reuters.

|

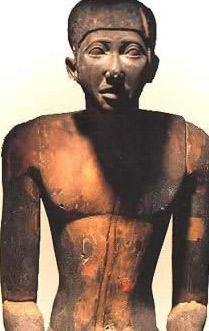

Imhoptep.

Image:

www.touregypt.net |

As you get older the thought that the years are running

out creates a compelling interest in health and medical

matters. Asking after the wellbeing of friends and

family becomes an extended part of any conversation. Too

many acquaintances disappear as their body parts give out.As you become more dependent on health and medical

services, you begin to search for more information in

the books on your shelf. The copy of an old St Johns

Ambulance First Aid Book, with drawings of men with

moustaches and broken arms in slings, and the medical

section of a forty-year old Pears Encyclopaedia

now no longer offer reliable answers.

Where do you go now for information on what’s wrong with

you? How is the health field responding to new ways of

doing things in the 21st century? How are

health industry developments affecting those who provide

dedicated service in this specialised field?

THE HEALTH FIELDWe have come a long way in learning how to deal with our

bodies. [i]

Medical practice is said to have begun with the Egyptian polymath, Imhoptep, who offered diagnoses and

treatments for 200 diseases in 2600 BC. His capabilities

as a doctor were no doubt reinforced by his other roles

as Chief Carpenter, Chief Sculptor, and Maker of Vases

in Chief. Two thousand years later, the Greek physician

Hippocrates introduced ethics by writing the Hippocratic

Oath.As civilisation emerged from the Middle Ages,

the medical profession continued to evolve. Women

began to play a more

influential role in the practice of medicine because of

the acuteness of their observation. Dr Mary Walker

changed views about senseless limb amputations during

the American Civil War. Florence Nightingale was

instrumental in reforming hospitals and the training of

nurses.

Some who set out to become doctors turned to other

professions because they couldn’t stomach some of the

things they needed to do. The French composer Hector

Berlioz, for example, on his first encounter at carving

up a dead body as a medical student, “leapt out of the

window and fled as though Death and all his hideous crew

were at [his] heels.” [ii]

After the

first painless surgery with general anaesthetic on a

live body was performed in 1846, new medical milestones

appeared at breathtaking speed.

Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928.

In 1967,

Christiaan Barnard successfully transplanted a human

heart. Louise

Brown, in 1978, became the first test tube baby. We have

already witnessed in quick succession during the 21st

century the development of robotic surgery, face

transplanting and human cloning. In

2013, the first baby in the United States was cured of

HIV. There is speculation that some visits to a doctor

will in future be a thing of the past because your

doctor will provide advice using Skype.

Today’s health and medical industry is a complex web of

forces.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO),

countries spend more than US$4 trillion on health.[iii]

International health programs attempt to increase

longevity, eliminate inequities and persuade citizens to

look after themselves. The WHO’s

Millennium Development Goals aim to reduce child and

maternal mortality, improve nutrition, reduce mortality

due to HIV infection, tuberculosis and malaria, and

increase access to improved drinking water sources.[iv]

There are economic conundrums. Increased

spending on health by some countries has put pressure on

other national government programs. However, state and

local governments depend on national government support

to sustain local economies.

Cutting

health care costs is politically difficult.[v]

These pressures are evident in Australia, where

healthcare expenditure reached $134 billion in 2012. It

is increasing at twice the growth rate of GDP.[vi]

According to IBISWorld, the sector employs almost

780,000 people (6.8% of total employment). The growth in

the demand for services is a response to an ageing

population, lifestyle-related diseases, a free public

health system, growing household incomes and new

healthcare technologies.[vii]

About 70% of health expenditure is in the public sector.

There is a strong emphasis on primary care through

general practice, supported by Medicare.

The federal government’s attempt to implement healthcare

reforms is navigating the minefields of Australia’s

federated system and adversarial politics. In June 2013,

a series of articles in the Sydney Morning Herald

reported tensions between the public and private health

systems, the games being played between federal and

state governments, hospital budget pressures and

four-year waiting lists for elective surgery.

There is a medical underbelly. This year, the Global

Mail has been investigating the murky relation

between drug companies and doctors. It reports that, in

a worldwide pharmaceutical industry of $942 million,

pharmaceutical companies spend around $60 million a year

in Australia “educating” doctors. To work around the

bans on advertising prescription medications directly to

the public in Australia, the process of duchessing

doctors involves “ever-so-slight

culinary conflicts of interest”, free overseas trips,

lucrative consultancies and speaking gigs. Many doctors

admit to an obligation to return favours.

According to the medical journal

The Lancet

this is creating a “moral decay”. Patients may be given

drugs inappropriately. Expensive drugs are given

precedence over equally effective cheaper drugs. Without

access to transparent information, patients

do not know the extent of drug company influence.

Pharmaceutical promotional activities

push up health care costs. Efforts are underway to try

to limit the corrupting influence of pharmaceutical

payments on prescribing patterns.

Dr Ben Goldacre, a UK epidemiologist, says there is a

problem with the information architecture of

evidenced-based medicine. His book Bad Science

tackles misinformation about science in the media. A

companion polemic Bad Pharma examines the toxic

results of decades of hidden clinical trials. Although

governments wrestle with vested interests to tighten up

dodgy pharmaceutical marketing practices, the process

gets lost in the bureaucratic labyrinth. We have our

heads in the sand about fixing the problem.[viii]

HEALTH INFORMATION

As countries combat expanding costs, moving into the

electronic realm is not only unavoidable, it is an

imperative. People now have ready online access to

general information about health and medicine. But

managing the information on which the industry operates

will be a major test.

Online trends

The Pew Internet Project’s

reports about online health information set the scene.[ix]

Just over 80% of US adults now use the internet, 87% own

a mobile phone, and 45% own smartphones. A large number

of adults (70%) use doctors and other health care

professionals as their primary sources of information or

support. But 60% also got information or support from

friends and family.

Among internet users, 72% look online for health

information and 77% of these began their search using

Google, Bing, Yahoo or some other search engine. Another

13% started their search on a site specialising in

health information, such as WebMD. The most

commonly-researched topics are specific diseases or

conditions and treatments or procedures. Nearly 30% of

online health seekers said they had been asked to pay

for access to something they wanted to see online, but –

significantly - only 2% said they did so.

Seekers of online health information fall into a number

of categories.

- Adults with a chronic condition - 45% of US adults who

have at least one chronic condition such as high blood

pressure or diabetes.

- Adults with a disability - 27% of US adults live with a

disability; 42% of these look online for health

information.

- Older adults - 75% of adults are aged 65 years or older;

54% of adults in this age group use the internet; but

only 12% of this group own a smartphone. Around 30% of

adults in this age bracket look online for health

information.

- Caregivers -

39% of US adults

provide care for a loved one. 79% of caregivers have

access to the internet. Of those, 88% look online for

health information.

People turn to different

sources for different kinds of information. When they

have technical questions, professionals hold sway. When

a situation involves more personal issues – such as how

to cope or get quick relief -- non-professionals are

preferred. A small number of adults use technology to

track their health data, such as blood pressure, blood

sugar, headaches, or sleep patterns.

General reference sources

People now have ready access to general information

about health matters. As the Pew Internet Project

outlined, Google and other popular search engines will

be the first ports of call for most. Some will turn to government sites and other portals carrying the fingerprints of authority

such as Healthinsite (http://www.healthinsite.gov.au).

Some may have subscriptions to sites and mobile apps

like WebMD (http://www.webmd.com/)

and the Australian Mydoctor (http://www.mydr.com.au/).

Some will dig deeper by turning to the US National

Library of Medicine’s PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/)

and other digital resources. High

quality medical research and plain English summaries are

freely available from Wiley’s The Cochrane Library (http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/)

and its iPad app.

Your national, state, university or local library may

have the ALA Guide to Medical & Health Sciences Reference

and other printed sources and they will facilitate

access to online sources available from specialist

publishers and aggregators. For example, the

National Library of Australia’s e-resource collection of

freely available, licensed or onsite titles includes

Australasian Medical Index, Australian Institute

of Health and Welfare, Australian Medical

Pioneers Index, Australian Public Affairs

Information – Health, Australian Sport Database

Medical Subset, EBSCO’s Consumer Health Complete,

Drug Database, Encyclopedia of Australian

Science, Encyclopedia of Bioethics,

Encyclopedia of Science and Religion, Free

Medical Journals, Gale Encyclopedia of Science,

HealthInsite: Health Information for Australians,

Health and Society Database, Health Source

Nursing Academic Edition, Health and Wellness

Resource Gentre, HIV/AIDS Database,

Informit e-Library: Health, ISIHighlyCited.com,

MasterFILE Premier, Medlineplus Health

Information, Merck Manuals, PubMed Central,

and Rural and Remote Health Database.

Sector data and patient records

Managing industry data and patient records

electronically is widely seen as a solution for

responding to pressing needs. Better information will

help governments decide where to spend their money.

Better information may help improve productivity in a sector that attracts an

increasing proportion of public expenditure.

Solutions will involve the application of general

principles of information engineering and data

management on a grand scale and addressing major

impediments.

Since 2000, an increasing number of international

guidelines and performance indicators have guided high

level global action. In the United States, the recent

release of database-generated information on

charges in American hospitals revealed “an incoherent

system in which prices for critical medical services

vary seemingly at random -- from state to state, region

to region and hospital to hospital.” Some commentators

anticipate that making this information available is

unlikely to bring swift and radical change to pricing,

but they acknowledge that at least it is a good start.[x]

A report by the Sax Institute for the NSW Mental Health

Commission has found that more than $10 billion is being

poured annually into mental health treatment despite an

“information vacuum” about whether the treatments

represent value.[xi]

Improved productivity depends to some extent on

minimising errors. Most people you know will tell

stories not only about the skill and dedication of

health professionals, they will also complain about

medical misadventures. The Institute of Medicine claims

that 7,000 Americans die each year from preventable

paper prescription errors.[xii]

A few years ago the US Pharmacopeia MEDMARX database was found to have

176,409 medication error records, of which 25% involved

some aspect of computer technology as one of the causes

of the errors. A study in the Internal Medicine Journal showed that 10% of

patients at Maroondah Hospital in Melbourne left

hospital with the wrong diagnosis in their medical

records and half of patient records were missing

significant clinical information.[xiii]

According

to Sandra Boodman, the number of errors – through

misdiagnoses, medication errors and surgery on the wrong

patient or body parts – is high in America, but

addressing the issue is a challenge because it is

difficult for doctors to admit mistakes when their

reputations are at stake.[xiv]

Costs

are viewed as a major barrier to the widespread adoption

of e-health systems. Even after the initial expenditure

on implementation, there are ongoing maintenance and

training costs. Local GPs in particular may experience

difficulties in making the investment. Financial

incentives are needed. Despite evidence of cost savings

in some settings, doubts have been expressed about the

return on investment.

According to the New York Times, doctors and hospitals struggle to make

new records systems workwhile major vendors of systems reap enormous rewards.[xv]

Connecting medical records

involves sorting out complex privacy considerations.

There have been some legitimate fears and examples of

breaches of privacy and confidentiality.

Some doctors have expressed concerns that increased use of electronic health records

could expose them to an increased level of malpractice

litigation. The US Government Accountability Office

reported a few years ago that there is a "jumble of

studies and vague policy statements but no overall

strategy to ensure that privacy protections would be

built into computer networks linking insurers, doctors,

hospitals and other health care providers."[xvi]

Making health information available will involve

clarifying protocols for sharing data on a number of

levels, from complete openness to fully controlled

access.[xvii]

There have been suggestions that unintended adverse consequences have been caused by

system design deficiencies.

Improving the way the data is presented is seen as a

major challenge.

Health data standards, privacy laws, and the nature of

health systems complicate the design process. In an

effort to combat this problem, the US Department of

Veterans Affairs recently embarked on a Health Design

Challenge (http://healthdesignchallenge.com)

to assist in building open source design solutions for

patient electronic records across the country.

Suggestions are now being incorporated in Veterans

Affairs hospital systems.[xviii]

The need for better information engineering comes at a

time when the field of health informatics is in the

formative stages of its development. As a discipline

that embraces information management, knowledge

management, project management, ICT, clinical

informatics, health records and other topics, the

adoption of standards will be at the centre of its

deliberations. Yet, according

to John Kuranz and Barbara Gilles, purveyors of health

systems “manoeuvre to occupy or invent the standards

high ground and to capture the attention of the

marketplace, but they often bring ambiguity to the

discussion of process and confusion to the debate over

performance.” They cite the International Statistical

Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems

and the American Medical Association’s Current

Medical Terminology among other language systems

heavily used, but further work, they say, is needed.[xix]

IT

Applications in Healthcare Technology

(ICS 35.240.80 IT) is one of a number of standards

covering health informatics. Standards Australia has

technical committees

working locally on the issue.

Creating sector-wide commitment to government-led

e-health systems is perhaps the major challenge. Glen Tullman, writing on the situation in the United States,

says the process of getting doctors to move into the electronic realm has

been

arduous and there isn’t conclusive evidence

that the use of electronic health records improves

patient care quality. Quoting a report from President’s

Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, he says

the impact of IT on health care over the past decade has

so far been modest. More physicians need to become part

of the system. The records need to be connected to each

other. And the systems that have already been installed

need to work better before it will help doctors,

patients and others improve health.[xx]

In Australia, a national e-health strategy, involving

the development of a shared electronic health records

system to address existing fragmentation, duplicate

effort and data inconsistencies, is being rolled out.

But the project is currently suffering from challenges

around the level of computerisation,

interoperability and the skills needed to make it work.[xxi]

The National E-Health Transition Authority

(http://www.nehta.gov.au/) has been established to lead

the uptake of e-health solutions and accelerate their

adoption. Health Direct Australia (http://www.healthdirect.org.au/)

has been set up to manage telephone health services, health information

websites and clinical governance structures to

streamline patient enquiries.

The Centre for Health

Record Linkage (http://www.cherel.org.au/)

is indicative of efforts underway to assist in

connecting researchers and policy makers to linked

health data. The National Broadband Network and other

technologies have the potential to revolutionise the

health sector.LIBRARY, ARCHIVAL AND MUSEUM SERVICES

Libraries, archives and museums have in the past been

good places for finding out what makes you tick. For

more than two centuries they have rendered valuable

services to the medical profession and the public at

large. In the age of ubiquitous computing, how are their

services being affected by online imperatives?

International libraries, archives and

museums

The largest biomedical library in the world is the

National Library of Medicine in the United States (NLM,

https://www.nlm.nih.gov). It traces its origins back

to 1818, when Dr Joseph Lovell, the first Surgeon

General of the Army, began building a reference

collection in his office. The library flowered in the

second half of the 19th century under John

Shaw Billings, a surgeon who transformed himself into a

librarian.

The library now has numerous databases, including

Medline, which is freely available on the Internet and searchable via

PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/),

other information, images and tutorials.

The NLM works with the National Network of Libraries of Medicine

to provide regional support throughout the United

States. During the early 1990s, it provided funding for the Manual for Cataloguing

Historical Medical Artifacts Using OCLC and the MARC

Format, prepared by the Ohio Network of Medical

History Collections. It hosts the

History of Medicine Finding Aids Consortium

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/consortium/index.html, a

union catalogue of primary source materials found in

special collections and archives throughout the country.

Other major medical libraries and archives in the United

States, include the Countway Library of Medicine (https://www.countway.harvard.edu)

at Harvard University and the Medical History Library at

Yale University (http://library.medicine.yale.edu/).

The US National Museum of Health and Medicine (http://www.medicalmuseum.mil/)

was founded as the Army Medical Museum in 1862 during

the Civil War and has achieved accolades for its

research on

infectious diseases and other health problems. Its

library and cataloguing system formed the basis for the

National Library of Medicine and its collection

today consists of about 25 million artefacts, including

skeletal specimens, preserved organs, medical equipment,

and historic medical documents. Other notable museums

include the Mütter Museum at the

College of Physicians (http://www.collegeofphysicians.org/mutter-museum/)

and the Dittrick Museum at Case Western Reserve

University in Cleveland, Ohio (http://www.case.edu/artsci/dittrick/museum/).

The largest medical library in Europe is the German

National Library of Medicine

(http://www.zbmed.de/en/home.html), which operates as

the official European agent for the US National Library

of Medicine.

One of the oldest medical collections in Europe can be

found at the Museum of History of Medicine at the

University Rene Descartes, Paris.[xxii]

It opened in 1954 but traces its origins back to 1769,

when two rooms were devoted to “ancient collections” at

the Academy and College of Surgery.

A new book on medical museumsexplores the collections of 15 leading museums

in Europe and the United States.[xxiii]

And a list of London health and medical museums and

archives can be found at

http://www.medicalmuseums.org/.

Recent exhibitions in London have drawn attention to the

value of museums as places of education and research.

The popularity of the exhibition, Death: A Self-Portrait, presented by the Welcome Collection

(www.wellcomecollection.org)

stimulated plans for a £17 million expansion. At the Museum of

London Archaeology, the exhibition Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men http://www.museumoflondonarchaeology.org.uk/)

explored scientific endeavours in the search for

knowledge about anatomy in the 19th century

and lifted the lid on the associated shadowy trade of

bodysnatching. Old bodies excited the public imagination

when the bones of Richard III were dug up from a

Leicester council car park and the British Museum

presented one of its oldest mummies, the Gebelein Man,

on a digital autopsy table.

The interests of libraries, archives and museums are

served by a large number of professional associations

and networks. Prominent among these is the Medical

Library Association (http://www.mlanet.org/), with

more than 4,000 members and partners worldwide. Other

groups of librarians include the Biomedical and Life Science Division and Pharmaceutical

and Health Technology Division of the Special Libraries

Association (http://www.sla.org/), Archivists and Libraries in the History of Health

Sciences (http://www.alhhs.org),

the Science, Technology and Health Care Roundtable of

the Society of American Archivists

(http://www.archivists.org/saagroups/sthc/index.html),

and the Canadian Health Libraries Association (http://www.chla-absc.ca/).

Among European bodies are the Health Libraries Group of

the Chartered Institute of Libraries and Information

Professionals,[xxiv]

a library group associated with the National Health

Service in the England (http://www.libraryservices.nhs.uk/),

the German Association for Medical Librarianship (AGMB) (http://www.agmb.de/)

and the Medical Museums Association

http://www.cwru.edu/affil/MeMA/memahome.htm)

International bodies include the International

Federation of Library Associations’ Health and

Biosciences Libraries Section (http://www.ifla.org/health-and-biosciences-libraries),

the European Association for Health Information and

Libraries (http://www.eahil.net/),

and the European Association of Museums of the History

of Medical Sciences (http://www.aemhsm.net/).Allied health and medical information groups overseas

include the International Medical Informatics Association

(http://www.imia-medinfo.org/new2/),

the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society

(http://www.himss.org/), the American Society of Health

Informatics Managers (http://www.ashim.org/),

and the American Health Information Management

Association (http://www.ahima.org/).

Australian libraries, archives and

museums

Professional bodies in Australia have recently explored

issues facing their members.

Health Libraries Inc (http://www.hlinc.org.au/), in

partnership with the Australian Library and Information

Association, has published Questions of Life and

Death, a report on the value of health library and

information services in Australia. It reports that,

despite a significant increase in users and high levels

of satisfaction in services, the budgets of services,

their staffing levels and floor areas have declined.

Reductions in staff hours have had a detrimental effect

on services. There is uncertainty about the future.[xxv]

ALIA’s own group, Health Libraries Australia

(http://www.alia.org.au/groups/HLA),

has published

Health

Librarianship Workforce and Education: Research to Plan

the Future,

drawing on similar reports on the changing circumstances of health

librarians overseas, to describe the situation here. The

expectations and habits of consumers of health

information have changed. Traditional library work is

diminishing. Professional boundaries are blurring.

Emerging areas of work are being claimed by other

professional groups.[xxvi]

Health Libraries Australia is developing a framework of

competency-based standards in the quest for continued

credibility.

Allied professional groups include the Chief Health

Librarians Forum Australia (http://www.fhhs.health.wa.gov.au/inforx/aboutus.html),

Health Informatics Society of Australia (http://www.hisa.org.au/),

Health Information Management Association of Australia (http://www.himaa2.org.au/),

Australian and New Zealand Society of the History of

Medicine (http://www.anzshm.org.au/),

the

Asia Pacific Association for Medical Informatics (http://www.apami.org/),

and the

Australasian College of Health Informatics

(http://www.achi.org.au/). It has proved difficult to

sustain a viable professional association in the museum

sector after the Health and Medicine Museums group

within Museums Australia folded up in 2006.

Health Libraries

Australia, based on listings in the Australian Libraries

Gateway, has estimated that there are 427 health and

medical libraries in Australia. They include facilities

in hospitals, universities, research institutes,

pharmaceutical companies, government departments,

regional health services, professional colleges,

not-for-profit and community organisations, and parts of

public library services. The Guide to Health and

Medicine Collections, Museums and Archives in Australia,

published by Museum Australia’s Health and Medicine

Museums division in 1999, listed 185 specialist

collections and more than 200 other collections with

health and medical material.

Australian health and medical museums were recently

explored in Museums Australia Magazine.[xxvii]

Their rich variety are exemplified in the Medical

Heritage Trail at the University of Sydney, where 19

museums, buildings, libraries, monuments and artworks

are located on campus, including the Pathology Museum’s

Interactive Centre for Human Diseases (http://sydney.edu.au/medicine/pathology/museum/).

At Museums Australia’s national conference in May 2013,

Jacqueline Healy outlined exciting building plans and

collection management strategies that tie together

a number of notable collections managed by the

University of Melbourne (http://museum.medicine.unimelb.edu.au/).

Museum, library and archival services in hospitals

include the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital (http://www.sswahs.nsw.gov.au/rpa/museum)

and Sydney Hospital, the oldest in Australia, where the

Lucy Osborn-Nightingale Museum, operating with

volunteers, has a morbid anatomy collection and

historical material.

Collections and services that have been developed by

professional bodies include the Harry Daley Museum and

the Richard Bailey Library of the Australian Society of

Anaesthetists in Edgecliff, Sydney

(http://www.asa.org.au), and its counterpart in

Melbourne, the Geoffrey Kaye Museum of Anaesthetic

History at the Australian and New Zealand College of

Anaesthetics (http://www.anzca.edu.au/ ). The Royal

Australian College of Physicians’ History of

Medicine Library, with approximately 40,000 items and a

collection of antique medical instruments (http://www.racp.edu.au/page/library),

is promoted as Australia's most significant collection

of medical history.

Substantial collections of diverse material are also

found in national and state institutions, For example,

Museum Victoria (http://museumvictoria.com.au/) has

general medical and surgical equipment used by Sir

Edward "Weary" Dunlop, research equipment and medicinal

samples from the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories,

1918-1984, and other formed collections of Melbourne

medical and dental practices. The National Museum of Australia (http://www/nma.gov.au)

has Fred Hollows’ personal collection and objects from his trachoma program, as well as

Australian Institute of Anatomy collections,

comprising Aboriginal human ancestral remains

once housed in the building that is now home to the

National Film and Sound Archives. Asylum patient records

and other documentation are held by State Records NSW.[xxviii]

Pulling data together to make the richness of these

collections more accessible has some way to travel.

Research Data Australia (RDA,

http://researchdata.ands.org.au/) lists nearly 800 data

sets and collections in the area of health and medical

science. Trove (http://trove.nla.gov.au/),

already populated with relevant information from RDA,

libraries and commercial databases, is keen to improve

its coverage and welcomes discussions about exposing

specialist collections to the national discovery

service.

As reported in Online Currents in 2012, the

National Broadband Network has led to regional digital

hubs that offer potential for new relationships between

local libraries and health services.[xxix]

THE DIAGNOSIS

Medicine is a speculative art that relies on scientific

information. Good health and the mitigation of diseases

are in the hands of patients as well as doctors. Some

doctors think patients are an

essential member of the clinical care team.[xxx]

The decision by Hollywood star Angelina Jolie

illustrates the point. In deciding to have a double

mastectomy to minimise the risk of future cancer evident

in her family history, she underscored the need for

clear information, good communication, shared

responsibility and a dose of courage.

Governments around the world have initiated e-health

strategies to help doctors to diagnose ailments and give

patients a better understanding of what’s going on with

their bodies. There have been teething problems in

implementing e-health systems and there are barriers

that need to be overcome to sort out underlying

problems.

Those working in libraries, archives and museums in the

health and medical field, like their colleagues in other

fields, face ongoing challenges. Myriad professional

groups search for greater unity of purpose. In a world

where the services of intermediaries are being reshaped,

there are fresh opportunities for those involved in

constructing systems and services that lead governments,

doctors and patients to online resources.

Endnotes

Bronia Renison, Director

Library Services, Townsville Health Library,

provided a number of useful suggestions on sources

and style.

[ii]

Fitzharris L, “Mangling the Dead: Dissection,

Past and Present,” The Lancet, 12 January 2012.

[xi]

Corderoy A, “Assessment of Mental Heath

Treatment Hurt by Lack of Data”, Sydney Morning

Herald, 13 June 2013

[xxiii]

Medical Museums: Past, Present, Future; edited

by S J M M Alberti and E Hallam, The Royal

College of Surgeons of England, 2013

[xxvii]

Bentley P, “Australia’s First Hospital and the

Landscape of Health and Medical Museums Today.”

(2012) vol 21 no 2 Museums Australia Magazine:

34-36

[xxix]

Bentley P, “Reinventing Libraries for the Mobile

Flaneurs: The Odyssey Continues” (2012) 26 OLC

295

[xxx]

Gray, JAM. The

Resourceful Patient (eRosetta Press, Oxford

2002

Non-commercial viewing,

copying, printing and/or distribution or reproduction of

this article or any copy or material portion of the

article is permitted on condition that any copy of

material portion thereof must contain copyright notice

referring "Copyright ©2013 Lawbook Co t/a Thomson Legal

& Regulatory Limited." Any commercial use of the article

or any copy or material portion of the article is

strictly prohibited. For commercial use, permission can

be obtained from Lawbook Co, Thomson Legal & Regulatory

Limited, PO Box 3502, Rozelle NSW 2039,

www.thomson.com.au

p

|